While researching for my next book, "Lifting the Veil on Copies of Stone Tablets Found by William Niven," I was reacquainted with the implication that James Churchward was responsible for sullying the reputation of Niven by publishing images of his tablets in the 1926 cult classic, "Lost Continent of Mu."

While I certainly have no quarrel with Mr. Wicks or Mr. Harrison; if James' translations/interpretations of the tablets really provoked the controversy that overshadowed Niven's other great accomplishments, does James bear responsibility?

From the preface of

Buried Cities, Forgotten Gods, William Niven's Life of Discovery and Revolution in Mexico and the American Southwest, the biography of William Niven:

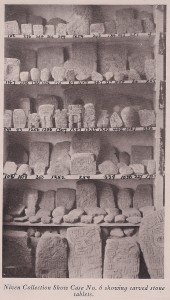

By 1910 Niven's interests shifted to the Valley of Mexico,

where he was the first person to recognize that a stratigraphic

approach to the valley's archaeology had chronological impli-

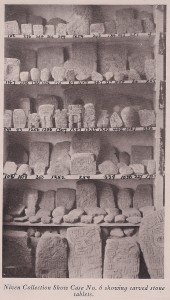

cations. In 1921 Niven unearthed the first of what would be-

come a collection of more than twenty-six hundred inscribed

stone tablets from various sites in the Valley of Mexico. Because

they are unlike any other artifacts recovered from the valley,

their authenticity is still not fully resolved. The controversy

over these inscribed tablets, especially after a number were

published by James Churchward in his occultist The Lost Conti-

nent of Mu (1926), provides a valuable look at the divergent

views regarding the origins and development of native Ameri-

can cultures current during the 1920s and' 30s.

The same book provides that James never met or corresponded with Niven until after Niven wrote him a letter dated September 19, 1927 (page 238,) which is after the publication of the 1926 "Lost Continent of Mu Motherland of Men." Prior to James' correspondence with William Niven, James' only access to Niven's discoveries would have been through newspaper articles written on the subject. James would have had to see them somewhere before he could include them in the 1926 book. As shown in my book, "

Lifting the Veil on the Lost Continent of Mu Motherland of Men", almost the entirety of chapter 11 is contained in one article in James' scrapbook, along with the only images shown of Niven's tablets, which indicates that Niven's promotion of his Mexico City discoveries (in a newspaper article) was ultimately responsible for their inclusion in the 1926 "Lost Continent of Mu Motherland of Men."

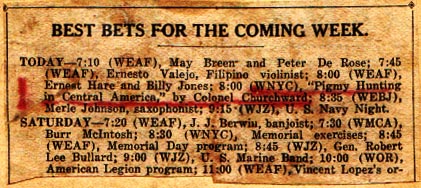

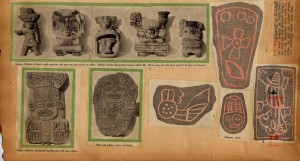

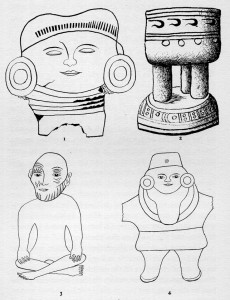

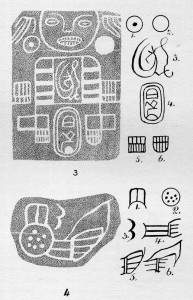

From Lost Continent of Mu Motherland of Men page 114:

RELICS FROM NIVEN’S LOWEST CITY 1. Egyptian head. 2. Ancient Grecian vase. 3. A toy. 4. Little Chinaman

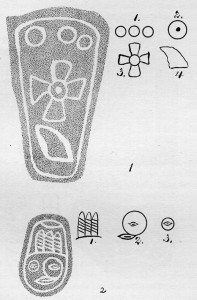

From Lost Continent of Mu Motherland of Men page 221:

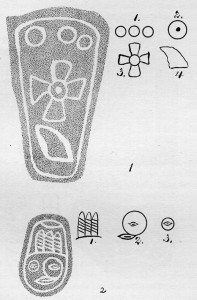

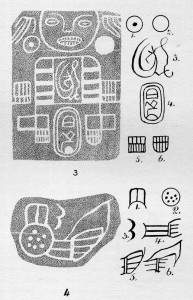

Courtesy of the Dearborn Independent

TABLETS FROM NIVEN’S MEXICAN BURIED CITIES. SECOND CITY

From Lost Continent of Mu Motherland of Men page 222:

Courtesy of the Dearborn Independent

TABLETS FROM NIVEN’S MEXICAN BURIED CITIES. SECOND CITY

Another random fact is William Niven and James Churchward were mentioned in a 1931 article entitled "Tracing the First Love Story Back to Ancient Mexico" from the Newspaper Features Service:

"In despair, only a few weeks ago, Niven sent it to Colonel James Churchward of London, distinguished traveler, explorer and archaeologist, and member of the Royal Society. Colonel Churchward has spent fifty years of his life delving far into antiquity, a great part of this time in learning the most ancient languages of man in India and Thibet.

Colonel Churchward was delighted to be entrusted with the task of deciphering what was

so closely related to a literary work of his on a continent which he holds has been submerged in the Pacific – and he was greatly gratified to find himself wholly familiar with the symbols used. These symbols were in use many thousands of years before the time of Moses.

One might wonder the source of such an article (included in James' scrapbooks) that paints 'Colonel' James Churchward in such high standing. The readers will have to answer the question themselves.

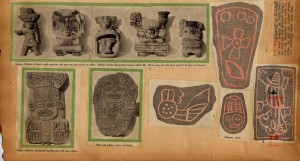

From James' scrapbook under "Niven's Buried Cities":

Newspaper clipping from James Churchward's Scrapbooks

Subsequent publication of Niven's discoveries in the 1931 "Children of Mu," 1931 "Lost Continent of Mu" and the 1933 "Sacred Symbols of Mu" are a direct result of Niven sending rubbings or tracings of the tablets to James for interpretation. While I can't vouch for the veracity of the translations, James simply engaged in what he was asked to do, interpret the tablets. None of the tablets were discovered after James became aware of them, so there can't be any accusations James Churchward is involved in any

hoax concerning these tablets (other than he may not have translated them properly.)

It should be mentioned that James Churchward was not the only one to hazard a guess as to the meaning of the tablets that Niven found. As mentioned in

Buried Cities, Forgotten Gods, William Niven's Life of Discovery and Revolution in Mexico and the American Southwest, Ludovic Mann (1869-1955), Glascow archaeologist, wrote to Niven:

Quite similar carvings have been found in the Old Hemisphere...

Buried Cities, Forgotten Gods, William Niven's Life of Discovery and Revolution in Mexico and the American Southwest, page 233

and John Cornyn (1875-1941), specialist in Aztec literature, deciphered the iconography on the some of the tablets and placed them in the context of a Mexican cultural discoveries.

Buried Cities, Forgotten Gods, William Niven's Life of Discovery and Revolution in Mexico and the American Southwest, page 236

Although Niven's

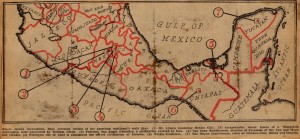

Guerrero collections are now in the American Museum of Natural History, the Peabody Museum of Harvard University, and elsewhere, the location of his finds from Santiago Ahuizoctla, Hacienda de Leon, Remedios, and Chimpala (the tablets discussed in

Copies of Stone Tablets Found by William Niven at Santiago Ahuizoctla near Mexico City) is unknown. Other researchers continue to search for these tablets, but it appears (for now), that the only way we have to research them is to look at the available images that remain (see below.) The tablets existed, that part is assured. Whether or not those that created them had the same meaning as interpreted by James Churchward is quite another matter.

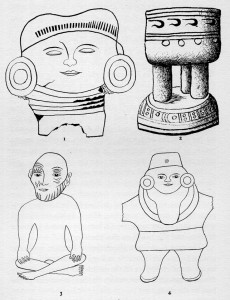

From 'Children of Mu' (facing page 41)

btw,

Buried Cities, Forgotten Gods, William Niven's Life of Discovery and Revolution in Mexico and the American Southwest has more photographed tablets than James Churchward shows in his books.

Certainly more is to be written about James' 'translation' of William Niven's discovery of 2600 tablets, especially if (and when) they again surface. Hopefully, the sensationalism will subside soon thereafter and permit an opportunity for serious academic research that will answer the questions. As indicated earlier, a knowledgeable expert already recognized and identified elements of Niven's discoveries within standard Mexican cultural iconography. Just because the tablets are connected to the lost continent of Mu should not imply they are a hoax or should not be studied to ascertain the truth. Such a bias helps keep people in the dark about early Mexican history and stifles discussion.

Jack Churchward