After doing another search for James' Churchward's book, "

Fishing Among the Thousands Islands", I came across what appears to be an early short story by James that was published in "

Recreation" magazine in March 1895. It was subsequently scanned by Google Books. I am not sure that it is auto-biographical, but it does provide a glimpse of the difference in speech over the past 110 years. A review of James' book, "

A Big Game and Fishing Guide to Northeastern Maine" written in 1897 has already been accomplished

here.

Readers should note that James' title is "C.E.", probably for Civil Engineer.

From "Recreation" Volume II Number 3 March 1895

By George O. Shields, American Canoe Association, League of American Sportsmen

INDIAN JOE, A TALE OF THE THOUSAND ISLANDS

J. Churchward, C. E.

During the summer of 1888 we spent three months fishing among the Thousand Islands. We were lucky beyond our greatest expectations. Nearly every day we were rewarded with fine catches of bass and pickerel, with an occasional muskalonge. The appearance of the latter always called forth warm and hearty congratulations, and well it might, for only the lucky and skillful disciples of Walton succeed in overcoming and safely landing these gamy monsters of the deep.

One fine November day, being within a few miles of the river, we determined to run up to Clayton and try one last conclusion with the finny tribe before the winter finally set in. On arriving at Clayton, I hunted up my old guide, Indian Joe. He is one of the toughest looking pieces of humanity I have ever seen; but his looks belie him. In truth, he is as gentle as a child; as brave as a lion; always trustworthy and obliging. His age is doubtful. He does not know it himself; and his nationality is more doubtful still. He has always been regarded as a half-breed by those who know him-as probably having a French father and an Indian mother- but this is conjecture. Joe says he does not recollect either parent.

One thing is certain: Joe knows the islands better than any other man living.

No other guide knows so well where to take his patrons for big fish and plenty of them. His boat, the "Queen of the Islands," is always neat and clean, while the oars and sail are daily recipients of his careful attention. One need only be with him once, in a good gale of wind, to feel ever after perfectly secure in his care, under any circumstances. The elements do not appear to affect Joe in the least, whether zephyr-like breezes or howling gales blow.

He has a faculty, when sailing his boat in a wind, of being able to get it on a big roller or white cap, and then running along it as if it were a cork. Many a time I have been with him when a huge wave would come along, black and threatening, ready to burst on us and swamp us; so dark, so threatening and so near; yet nothing serious ever happened. While I would be shuddering at the black wall of water bearing down on us, Joe would simply, at the right moment, draw in or let off his sail, move a foot or two one way or the other in the boat, and the next instant she would be on top of the breaker, shooting along at lightning speed, without taking sufficient water to dampen our shoes. At such moments Joe appears unconscious of what he is doing, or where he is going. Like clockwork the skiff, as the breaker passes away from underneath her, falls back into her course. She seems to be guided by the will of the man rather than by his hand.

On the occasion of which I am about to write, Joe had many excuses for not wanting to go fishing. It was too late in the season, he said. All the big fish had worked their way up to the lake by this time. The wind wasn't right; it came directly out of the nor'west, and there was no wind so bad as that for fishing. The general aspect of the weather didn't look right; it was going to be dirty and blow hard; and trolling under such circumstances was simply an impossibility.

At last, Joe, seeing that all his excuses were of no avail, and that I was determined to make a trial at least, remarked that if we went over among the Canadian islands we might possibly strike a Muskalonge working his way up stream. So at 10 A. M., after wasting three of the best hours of the day, Joe made up his mind to try it. It meant three dollars to him, and that could not be picked up every day at this time of the year.

A lunch basket was packed and we went to the boat-house. There lay the dear old "Queen of the Islands," just as I had left her a month ago, looking as clean and saucy as ever. She deserved her name; no boat could ever sail past her in a breeze, and no wave could ever tumble into her while Joe was in command.

Joe's actions were strange this morning. He carefully tried a new pair of oars three or four times before placing them in the boat, and examined and felt the leather bindings over and over again. The sail was minutely examined, every stitch and binding being looked to. Finally that was placed in the boat also. Noting all this extra precaution, I asked Joe what was the matter. He answered:

"The weather gets dirty this time of year, without much warning. A careful man always tries his friends before he trusts his life to them."

At eleven o'clock we started with a light nor'westerly breeze, passed between Governors and Emery's islands, and then through the Eagle's Wings, to the head of the Grindstone. Sailing along the Grindstone, passing Club and other islands, we reached Hickory Flat. Here I thought we should get a strike, but was wrong. Joe seemed to think we should not find what we wanted on the flats, but rather in or alongside the deep channels. At Cement Point, Joe loosened out his sheet and ran down to Seven Tree Island. Here we let out the lines and fished the ground thoroughly, but without a strike. Then along the head of Leek Island. On arriving at Juniper Island we ran down through the channel and lunched on the lower point. Joe is an excellent cook, but took twice as long as usual to-day in preparing the meal; yet I must acknowledge it was one of the best he ever presented to a hungry patron.

We made another start at three o'clock, taking first the channel between Juniper and the Northern shoal, and then the channel on the south side of Huckleberry. Here we struck a brace of good sized pickerel; but as Joe was after bigger game, we took the head of Kelaria. Passing completely around this island we worked back to the north side of Huckleberry and struck the Cow's Horn Reef, which lies alongside the main channel, passing completely around it without a strike. Joe said:

"That' strange. I saw an old soaker on top the water here yesterday. Try a different spoon. Put on nickel and brass instead silver and copper, and make 'em 8s instead of 9s; I guess the old fellow filled up yesterday. Only wants a small bit to-day."

The change of spoons was made, and back we went around the Horn again. Just as we were turning the point, on the channel side, the inside line straightened out a bit, but slackened again immediately. We turned, and going down Joe suggested that I reverse the spoons, putting the brass one inside and the nickel on the outside, for he guessed the old fellow had a taste for perch today. The second change was made, and on we went around once more. Just as we came to the point, Joe quickened his pace, and was in the act of turning when the inside line straightened. Down went the rod to the water's edge, and then a terrific shake of the rod, followed by a splash behind, like that of a rock falling into the water. The old fellow was hooked, and had just made his first break. After half an hour's tussle we succeeded in landing him - a beauty of 42 pounds.

It was now half-past four, and Joe looking up, said:

"We are close to Gananoque. My cousin is sick. I would like run in and see how he is."

So off we went. At half-past five he came back to the boat and reported his cousin better. One more start, and this for home. Already it was getting dark, and the moon being only half full, with a cloudy sky, there was not much promise of any light to pick our way through the islands.

To my astonishment Joe, instead of taking a direct course for home, started up river, keeping close to the mainland. I inquired where he was going. He said he intended to keep close to the mainland until he got to Howe Island, then up alongside that until he could see Clayton Lights to guide him home. To me this was strange, for many a time I had come through the Admiralty Group when the nights were as dark as Erebus. But then Joe is always strange, and to question him would only have been to make him tell more lies. If Joe does not think it convenient to tell the truth, the only thing to be done is to wait and watch and see what he does next.

At half-past six we got up to the lighthouse, off the foot of Howe Island. Joe here drew his boat ashore and proposed going up to a farm house, the lights of which could be seen on the water. The owner, Joe said, was another cousin. He observed it was about time for supper, any way, and we could not possibly get home for two or three hours.

On arriving at the farm we found the table laid, and from the odor a good supper was in process of cooking. I was surprised to see that the table was set for one only, and apparently from the setting, some visitor was expected. A clean white table cloth, in the middle of the week, is a thing one does not expect to find in an ordinary farm-house, unless on some extra occasion. Then everything else was in keeping. Every one was dressed in his or her best, evidently expecting some visitor beyond the ordinary. Joe explained that he had sent up from Gananoque to say we should have supper here.

From the time we arrived until we left the house, at nine o'clock, Joe had so much to say to his cousin that I scarcely saw anything of him. On asking him where he had been, he said his cousin had been anxious to show him two new calves and a litter of pigs, and he had been down to the barn to see them.

Just before we started, being left alone again, I went to the front door to look out and see what the night was like. The clouds were heavy and flying fast. The rain was pattering against the windows, while the swaying and moaning of the trees showed we were in for a bad night. In the face of this, Joe proposed crossing the river in its widest and most exposed part, instead of going through the islands where we could at least have shelter, part of the way, from the raging storm.

While standing at the door looking at the racing clouds I overheard the following conversation: "Is he safe? Can you trust him?" Joe answered: "Sure; I've rowed him seven years. Him true gentleman I'd lay down my life on it. He never would do poor guide bad turn. He's safe. No, Bob, I feel safer with him than alone. But Lord it's a rough passage we'll have. How the wind does howl!"

There was something mysterious about this. I felt uneasy; calling Joe, I retired to the dining room. Joe soon appeared looking the picture of innocence and unconsciousness. I repeated the conversation I had heard, and demanded from him an explanation. He hesitated, looked around the room, up to the ceiling, and then to the floor. At last, in a sheepish way, he explained that he was taking back two bottles of Scotch whiskey to some friends in Clayton; as it was a dutiable article, if he got caught it might give him some trouble. He didn't suppose I'd give him away, and that was what he was telling his cousin. I thought it but a small matter, and concluded to make no objection.

We covered ourselves with our oilskins and sou'westers. Thus clothed we were fairly protected against the sleet and rain. About half-past nine we took the water. As the boat settled I noticed that her natural buoyancy was materially reduced and she sat deep in the water. I asked Joe if she hadn't a lot of water in her. He said:

"No, guess it's the pig over here. She's a beauty weighs 300 pounds."

He took to his oars and worked up in the lea alongside Howe Island, until we struck Chockrow flats. From here we could occasionally see the flicker of one of Clayton's electric lights. Joe looked carefully over his boat, shifted the pig back a little, hoisted his sail, and made straight for Hickory Island. As we left the land and began to catch the full force of the wind, the boat began to pitch and labor heavily. In less than ten minutes we were in a veritable boiling cauldron. The river was a continuous line of white caps. As soon as a wave broke the wind caught the foam, lifting it and carrying it along until it looked like a snow-storm. It froze and cut our faces and hands like needles. Water struck the side of the boat and came over. She was too heavy to rise quickly enough to prevent it. This kept me constantly bailing. Before we had gone a mile through this, I would have risked my eternal salvation to be back on terra firma once more. After three quarters of an hour's battling we reached the end of Hickory Island and ran under its lea, not a moment too soon, for with all my bailing we had fully six inches of water in the boat. Another quarter of an hour and we should have been swamped, in spite of me. We drew the boat up on the beach and let the water out; then I lit a cigar and rested for a time.

The rain began to let up and the wind moderated. Before starting again, Joe took out a Winchester rifle from a tarpaulin, loaded it and laid it down alongside his seat. Then he advised me to see that my own gun was handy, in working order and ready for use at a moment's notice. I was told to use it, too, if necessary. I thought this precaution simply absurd for a couple of bottles of whiskey, and a dressed pig. I told Joe that rather than fire a shot, I would pay the duty, if we were overhauled Then Joe said:

"This here pig happens to be 400 pounds of opium. If the officers catch us with that in the boat there's seven years for us, sure. I heard at Clayton, before we left, that detectives are on the job. Be careful as soon as we pass this island.

Here was I in a nice fix. In case of capture there was nothing to exonerate me. Seven years languishing in a prison was not pleasant to look forward to. Under the circumstances it took but a few moments to make up my mind. Rather than live in disgrace and confinement, guilty or not guilty, I would make a fight and sell my life, if necessary, rather than be captured.

At the American end of Hickory Island we stopped, took down the sail and rowed across to the first American rock, which Joe proposed to climb and survey ahead. We pulled in alongside of it and Joe was about to climb to the top when we heard voices from the other side:

"Can you see anything coming, Jack?"

"Not now, a few minutes ago I thought I saw a sail creeping along the lea side of Hickory, but the clouds closed over the moon before I could make out for certain. Well, I don't think it can be Joe, for bold as he is, he would not dare cross the channel in such a howling storm as we have been getting. I rather think he will run down to Hay Island, then along the foot of the Grindstone, and up by Robbins'. He would get shelter most of the way then. No boat with a load in her could have crossed the main channel in such a blow."

"Well, then, if he goes that way, Zip's cutter will get him off Frink's Bay, and if he should try to sneak down the mainland Sam's cutter will get him at Bartlett Point. If that black muzzled cuss can run through the lot of us tonight he's a smarter man than I ever took him to be. Who'd ever have thought that Mr. A. was mixed up in this job? That explains how the boys get rid of the stuff down in New York without leaving any traces. No one would ever have suspected him, and if he had not come up to attend to running off this cargo, he never would have been found out. This will be a fine haul tonight, boys, for we not only get the small fry, but the principal, too. What's that you say, Mike? Afraid of Mr. A?" Mike answered.

"Yes; I don't want him to draw a bead on me. He's a dead shot. I once saw him win a wager, up at Boxton Harbor, by cutting the string that held an apple, at 500 feet, with a Winchester. There isn't much fun facing a shot like that. You can take my tip; every time he pulls a trigger one of us will go to fill the bottom of the cutter. We are all six of us dead men before we get within a hundred feet of them, if he begins shooting. I wish I was out of this and back by my fireside, in Clayton."

"You're showing the white feather, Mike."

"No, t'isn't that; but when I think of Liz and the little ones, I don't feel at all anxious to get too near to Joe's Skiff. You all know me. I never shirked duty nor danger when 'twas honest. Didn't I go out on the broken ice to save old Tom, when none of you dared? No, I don't like this job. If I get knocked out who's to look after Liz and my babies and give them food and fire during the cold winter months? Boys, it's not worth it, all for the sake of a few dollars in or out of the country's pocket. Would the government take care of my little ones, if I go down tonight? I guess not. They would have to depend on charity and there's not much in that to keep them warm and hearty."

From the authoritative tone it was evidently the captain of the cutter who now spoke.

"We must put Mr. A. out of the way of doing us harm. When we run across them, we'll demand surrender. If they don't stop at once, give Mr. A a volley.

"Don't show the white feather, but when the time comes, shoot to kill."

This was interesting for me, to say the least of it. Here was I, absolutely innocent; yet being put down as the principal in a smuggling scheme. If caught, nothing could save me. I instinctively took my revolver and felt the trigger. At that moment I caught Joe's face which had a dark sinister smile on it. He shook his head and put his finger to his mouth as a warning; then noiselessly picked up his Winchester, and handed it back to me.

The clouds now thickened and it became inky dark. Joe noiselessly pushed off from the rock, took his oars and cautiously made for the Grindstone. Now for the first time I understood his care about the leather bindings in the morning. The leather being new, soft and spongy, perfectly muffled all sounds. We had just reached the side of the first little island, about 1,500 yards away, when the clouds cleared, the moon shone out, and we were discovered. The officers were at once under weigh and after us. Just as we reached the farther end of the island they gave us a volley. No harm was done; only one shot struck, taking a little chip out of the end of the blade of one of the oars. A moment later, we were round the point and out of sight. The clouds now came over the moon again and darkness favored us. Joe said:

"In three minutes we be safe!"

How, I could not see, but my faith in Joe was implicit and I felt at least a certain amount of security. Just ahead of us lay a group of little islands. Passing the first of these rocks Joe drew in behind it. The cutter had not yet appeared around the first island we passed. Then we made straight for another with a dwarf pine at its head. Passing around it, on the farther side, Joe ran into some rushes. He jumped out and told me to do the same; he then took hold of the bow of the boat and pulled it in through the rushes. On the inside was an archway in the rocks, just wide enough to let a skiff through and high enough for a man to pass under by stooping; but so low, in fact, that the tops of the rushes grazed he roof of the archway. This tunnel was not perfectly straight, but curved just enough to prevent any one seeing through it from either side. Our united efforts soon got the boat through, there being water enough to float her as soon as we got out. On the inside there was a basin or pocket of water about two feet deep and some fifty feet square. On the left side was a little sandy beach and a cave running back about 30 feet. This contained three or four logs, evidently put there to run a boat in on. At the end of the cave there was a crevice or crack in the rock, about four or five inches wide, which opened so that one could see everything in the direction of Hickory. As soon as we were thus housed, Joe went out and straightened up the rushes which had been bent down by our passage through them. Then he came back and took a peep through the rift.

"Here they come," he said. "I'll go up to the look-out."

I followed him. On the top there was an indentation so that one could lie there without being seen from the outside. We watched the cutter pass around and through the group, in every direction, examining closely every possible place where a boat might be hugging the rocks to avoid being seen. At last she came to our island, which, by the way, was one of the smallest of the group, rowed around it, then carefully looked into the rushes through which we had passed, but failed to discover the archway. Here the men rested.

"Well, boys," said the captain. "That cuss must have doubled around Coral Island and then back to Hickory, which is Canadian, and where we daren't follow. As we came down on one side he must have gone up on the other. As we showed out at the head he must have turned the foot; then getting the island between us and him he had a clear run to Hickory. We'll signal Sam, at Bartlett Point, that we've sighted our game; he will then be on a smart look out. Then we'll go back to our old hiding place and wait for him once more."

Two minutes later a rocket flew heavenward and passed within a few feet of us. It was answered by another from off Bartlett Point. Joe whispered:

"That's good. Now I know where the Bartlett Point cutter is."

Our friends now left us. I went down to the cavern and smoked a cigar. No one knows the full value of a puff of the fragrant weed who has not been in such a position as this. Joe remained on the lookout until he saw the cutter double round Coral Island.

A quarter of an hour afterward we hauled out our boat and set sail for the American mainland. The clouds were more broken. Joe said we must get a hustle on before it entirely cleared, or get caught by the Bartlett Point boat. With a fair wind, in 20 minutes, we struck the American mainland at the upper end of Colan's Flats. The moon had now sunk so low that by hugging the shore the high land prevented the moon's rays from striking on our sail and betraying us. Being out of the wind, the water was calm, so we ran down within 50 feet of the land. When within a quarter of a mile of the Point we saw a rocket go up from the Bartlett Point boat. Joe gave a start and held his breath. Could it be possible that we were again discovered? No; a few seconds later a second rocket went up. This, Joe said, was their signal that they were going farther up river, probably to lie under the Blankets to cut us off from crossing to the mainland from the south side of Hickory. They set sail and with the first opening of the clouds we saw their boat moving toward the Blankets. We were now getting close to the Point and out from the kindly shelter of the land, so Joe took down his sail and rowed. If the moon would only keep behind the clouds for five minutes we should be safe, but fate decreed otherwise. Just as our boat was off the Point, in the most exposed position, the clouds broke and the moon shone full on us. A shout from the cutter told us we were seen.

Joe laid to his oars. Down went their sail and after us they came with two pair of oars. Joe rowed in close to shore under the shelter of the trees. The cutter followed down as far as the Point, where we saw them stop. Joe did the same. Then they came along close to shore. Joe pulled his boat in underneath the branches of an overhanging tree which completely hid us. Just as they got directly off us, about 100 yards out, we heard one of them say:

"We're all wrong, boys, to hug the shore like this. He dodged in here, ran down a little and then straight out into the centre of the bay. While we are hunting for him in the dark, here, he will land his cargo safe at Buck Burns, and when we catch him the stuff will be gone."

The cutter then moved out and took the centre of the bay. We proceeded down cautiously close to shore. Every now and then they would stop to listen. Joe would do the same. We had a great advantage over them, because we could place them all the time by the sound of their oars in the rowlocks, while ours were muffled. We had got nearly down to the bridge when the moon once more betrayed us. The cutter was probably 1,500 yards to our left. A second later and they gave us another volley. We were not touched although we heard two balls strike the water ahead of us. Then there was a race for the bridge. Just as we came to the archway they stopped and fired again. One ball struck our mast as it protruded over the bow of the boat.

As soon as we shot the bridge, we turned clear around to the left, into some bulrushes, close to the piles, where it was utter darkness. Here we found another boat, with Joe's brother Bill and another man in it. Joe called out:

"Pull up creek, Bill, for life. They are close after me."

Bill was ready and waiting for this ruse. They started off, and just as Bill got to the first bend, the cutter came through the bridge. Bill shouted at the top of his voice:

"Pull, for heaven's sake, here they come," and then turned the rush point.

The cutter gave Bill, or the rushes, it's hard to say which, a volley, and rowed like mad after him. As soon as the cutter passed around the point, Joe pulled his boat back through the bridge and rowed toward Clayton until he came to a cottage with two lights in a window. Then he lit a lamp, swung it twice, when one of the lights went out. This was a signal to land, as everything was ready. We ran the boat up on the beach. A buggy with a pair of fast horses came out. In another minute that buggy was spinning away at the rate of 15 miles an hour, with those fatal packages that had been my terror for the last three hours. As soon as the buggy was out of sight, Joe pushed off his boat again. What a difference in her! She now rose like a cork to every movement of the water. The load was out of her and off my heart.

Joe hoisted a white flag, denoting that he had a muskalonge on board. His Winchester and cartridges must have accompanied the cases in the buggy, as they were not to be seen in the boat now. Rowing leisurely around to his boat-house, he proceeded to dock the "Queen," when two officers stepped out from the shadows and arrested us for smuggling. Joe simply laughed, saying:

"I guess you're away off."

Having got rid of this precious burden, I felt a little bolder and asked what they meant-what joke was it they were putting up on us; I was well known and had been fishing; my fish lay there in the boat. They wanted to know how it was that I had been out till 3 A. M. I answered by questioning whether they thought any one with common sense would have faced such a storm in a skiff. My duties called me back to New York in the morning, and I had to get across some time during the night, to catch the morning train.

After examining our boat in the most scrutinizing manner, one of the officers said:

"How in the name of Satan you fellows ever got through the cutters without capture beats me. They have been after you all night. Our information, from our detectives oh the other side, distinctly states that Indian Joe and a gentleman, unknown, took the cargo. You are free now, as we have nothing to hold you by, but we'll get you yet."

We housed the boat, took our fish and made for the hotel, which we found filled. The excitement of chasing a smuggler was too much for the inhabitants of this sleepy little village. Our muskalonge was weighed, labelled and laid out on a table in the office, while the kindly host dispensed hot toddy to the thirsty crowd. An hour later Bill came home in charge of the cutter. He had given them a great race, playing hide and seek among the channels and rush beds of the creek. To hold him the officers found was absurd, as he had been working at the Rock House up to nine o'clock, and was seen again about midnight going in the direction of his home; besides, there was nothing in his boat when captured to hold him on. A short time after the Hickory cutter's crew came in, having been attracted by the firing, off Bartlett Point and the bridge.

I took Mike over to the bar and gave him a toddy and something for his Christmas dinner, and then said to him:

"I don't want Mr. A. to draw a bead on me, he's a dead shot. I once saw him win a-"

Mike's hand was shaking like a leaf. He gulped down his toddy and made a rush for the door. Joe remained a while, but finally shook my hand and left, saying:

"Pretty stormy coming home, but that's what we expect this time year."

When at the door he turned and inquired whether I would like to go out in the morning and catch the mate of the spotted fellow that lay there on the table. I answered:

"I think not, Joe, it's too rough work fishing this time of year."

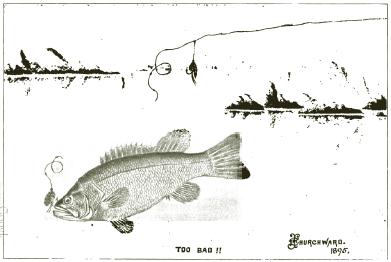

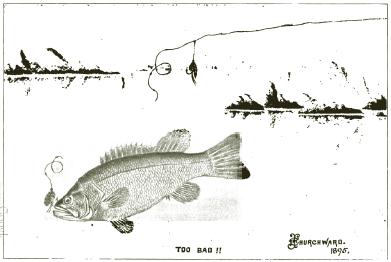

As an added bonus, that edition also had a picture drawn by James.

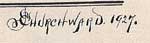

His signature/initials is/are different, as shown by the following comparison:

Signature from

'Recreation' article |

Signature from 1927

"Books of the Golden Age"

page 45 |